Fertility in Desert Females – Overview and Case Study

If you’re a Ball Python veteran, you have heard of (or experienced) the infamous saga of the Desert gene. Few morphs have blown up as big and fast as the Desert. This amazing mutation is simply packed with potential – a powerful combination of pattern shifting and clean up, adding a golden touch to nearly every combo.

If you’re a Ball Python veteran, you have heard of (or experienced) the infamous saga of the Desert gene. Few morphs have blown up as big and fast as the Desert. This amazing mutation is simply packed with potential – a powerful combination of pattern shifting and clean up, adding a golden touch to nearly every combo.

Initial Rumors

When the rumors started nobody wanted them to be true. “The females stay small”, “females are thin like ‘rat snakes'”, “there should be super Desert combos by now.” As people split on both sides of these whispers, few can forget the amount of drama this morph stirred up as its 2nd act. I personally paid BIG for two cutting edge Desert combos just before the controversy really took off.

First Data

In the ensuing years, the rumors of trouble with the females turned out to be mostly accurate. Many had trouble getting females up to breeding size, while others grew them up only to hit production roadblock. The best information from this time can be found at this thread on the BLBC forum. Lots of interesting details can be gleaned by sifting through the accounts of those who were on the front lines of experimenting with this problem. What is clear is people searched for answers to the problem and held out hope even as negative results piled up. An excellent step by step account that can be found from this time was by Albey at Albey’s “Too Cool” Reptiles. He gives a very detailed report of his 2000g female Desert slugging out. You can read his experience here. There were also breeders who would post details of breeding Desert females, but then not report the result.

Nearly all of these early attempts resulted in slugs. There was an early theory that it might be temperature related, (since most slugs are temp caused). When there were good eggs in the female, they seemed to be unable to lay them successfully and would either die or need surgical intervention.

Nearly all of these early attempts resulted in slugs. There was an early theory that it might be temperature related, (since most slugs are temp caused). When there were good eggs in the female, they seemed to be unable to lay them successfully and would either die or need surgical intervention.

Another idea was fielded that perhaps it would be necessary to grow Desert girls up to an unusually large size / age in order for them to be large enough to successfully pass full sized eggs.

I didn’t breed any Desert females during this time. As it became clear there was a real issue, I sold my females (and eventually my males) as pet quality animals. I kept one Pastel Tiger (Pastel Desert Enchi) female in the hopes that someday I would grow her up big enough to see if her size was a factor in the problem.

My Case Study

My Case Study

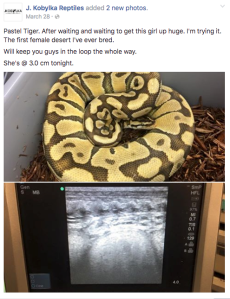

Fast forward to 2016, my Pastel Enchi Desert female was pushing over 3000g, larger than I’d ever heard attempted. I ultra sounded her with my other females and found that she had very large follicles even before being bred. That’s when I decided to put a single breeding on her and let her figure out what she wanted.

One thing of major frustration to me is that many people who dealt with Desert females did not come forward personally and give their account of what happened. Many stories were relayed 2nd hand. So when I discovered my female was likely going to be gravid I immediately shared that I would be updating my page on exactly what would transpire.

I felt that I was doing something unique by breeding a 3000g female, and it would be a different angle on the problem and maybe even have a different outcome.

I felt that I was doing something unique by breeding a 3000g female, and it would be a different angle on the problem and maybe even have a different outcome.

From the very start there has been a significant amount of interest and support, but also backlash. Some felt like it was very irresponsible to even attempt because “this issue has been put to rest”. Some felt like I must not care for the health of my animals if I was willing to put her at risk. To me this was ridiculous, as she is a very special snake to me that I had grown up for years even when there was no financial benefit to keeping her.

From the very start there has been a significant amount of interest and support, but also backlash. Some felt like it was very irresponsible to even attempt because “this issue has been put to rest”. Some felt like I must not care for the health of my animals if I was willing to put her at risk. To me this was ridiculous, as she is a very special snake to me that I had grown up for years even when there was no financial benefit to keeping her.

The health of the snake was paramount from the start and every intervention was on the table to ensure she survived. This hobby is built on hobbyists who believe experimenting and also growing their knowledge of these animals, including their issues! The day I stop trying to to seeking to understand is the day I no  longer have a passion for this hobby and my animals.

longer have a passion for this hobby and my animals.

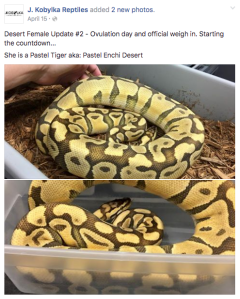

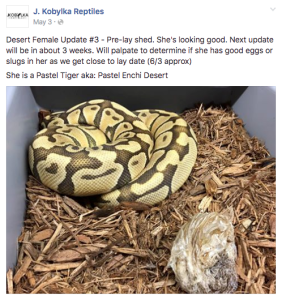

Everything leading up to ovulation went exactly as expected. She had a nice big ovulation and immediately started heat seeking coiled up as expected. Her post-ovulation shed was exactly 20 days after ovulation.

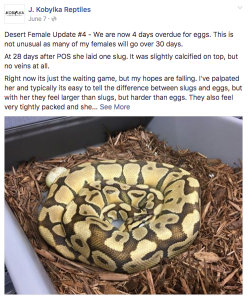

As she began to close in on her expected lay date (30 days after POS), I palpated her to see if she was likely full of good eggs or would slug out. Most of lumps in her felt like full sized eggs, but were very stationary and pressed together. I could not easily shift them around in her like a typical gravid female.

28 days after her POS, I found her with one slug laying outside of her coils. I actually felt relief because I felt that if she could push one slug out of her, that would be  an indication that she was capable of safely passing the rest of her clutch.

an indication that she was capable of safely passing the rest of her clutch.

Unfortunately that was the beginning of a very long wait. As more and more time passed I really despaired that this experiment would not turn out well for her. Making sure she pulled through healthfully became my #1 priority.

As she reached the mark of 30 days past her due date without resolution, I made arrangements to have the eggs surgically removed.

I want to give a big thank you at this point to Carlos of OTB Reptiles for his help through this process. He not only shared valuable information with me about his experiences with Desert females, but also put me in touch with a fantastic Vet that had successfully worked with egg bound Deserts. His efforts to help a fellow breeder in need shows the best qualities of the reptile community!

On July 4th she successfully underwent a procedure to remove her eggs. Dr. Atlas in Birmingham, AL did a fantastic job with her. He reported to me that the remaining 7 eggs in her were full size, but were stuck to the lining of Uterus to the point where they were nearly adhered and could not slide down to exit the female. He removed her eggs and uterus in order to complete the procedure.

Here are photos from her procedure day.

According to the vet, her eggs appeared fertilized and “normal” but were discolored and rotten from not being laid at the correct time.

Another very interesting point in speaking with the veterinarian is a different Desert female he had worked on had completely lacked a connection between the uterus and cloaca. The natural laying of the eggs would have been completely impossible regardless of size or circumstances in that instance. This also points to there being potentially multiple different issues regarding the reproductive systems of Desert females, any of which could present an obstacle to success.

My female is now healing up very well and is active and behaving completely normally. Even though this did not end up with success and healthy eggs, I’m very pleased that she is well and she will continue to be a pampered pet for the rest of her life.

Conclusions

I hope this is both an educational and cautionary case study for those who trying to understand this very unique mutation and the challenges it presents.

There appear to be multiple variations of fertility problems in Desert females ranging from inability to properly fertilize eggs, to inability to pass eggs / slugs for multiple reasons. To me, these challenges are great enough that it doesn’t warrant continuing to put these females through the risk and stress of breeding them.

Some have asked me whether I think it would be possible to remove the eggs at the correct time and hopefully they would be fertile. This is a possibility, however in my experience even under much more ideal timing and conditions, eggs that are removed from Ball Pythons have not successfully hatched (for unknown reasons).

Even if this were a real possibility, I would not advocate it, as we have plenty of amazing mutations to work with and putting an animal through this procedure on purpose would be taking it way too far in my opinion. There would have to be a significant prospect of Deserts producing naturally for me to even consider revisiting this issue.